Advertisement

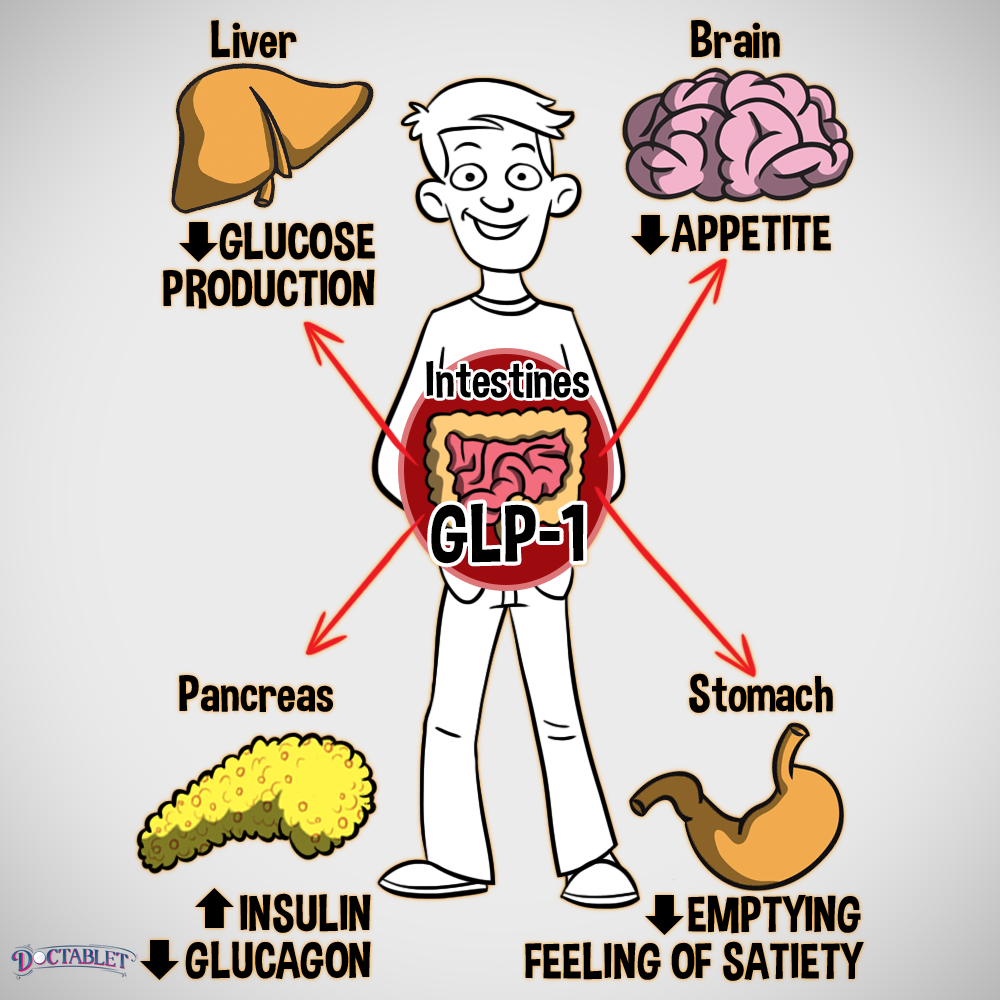

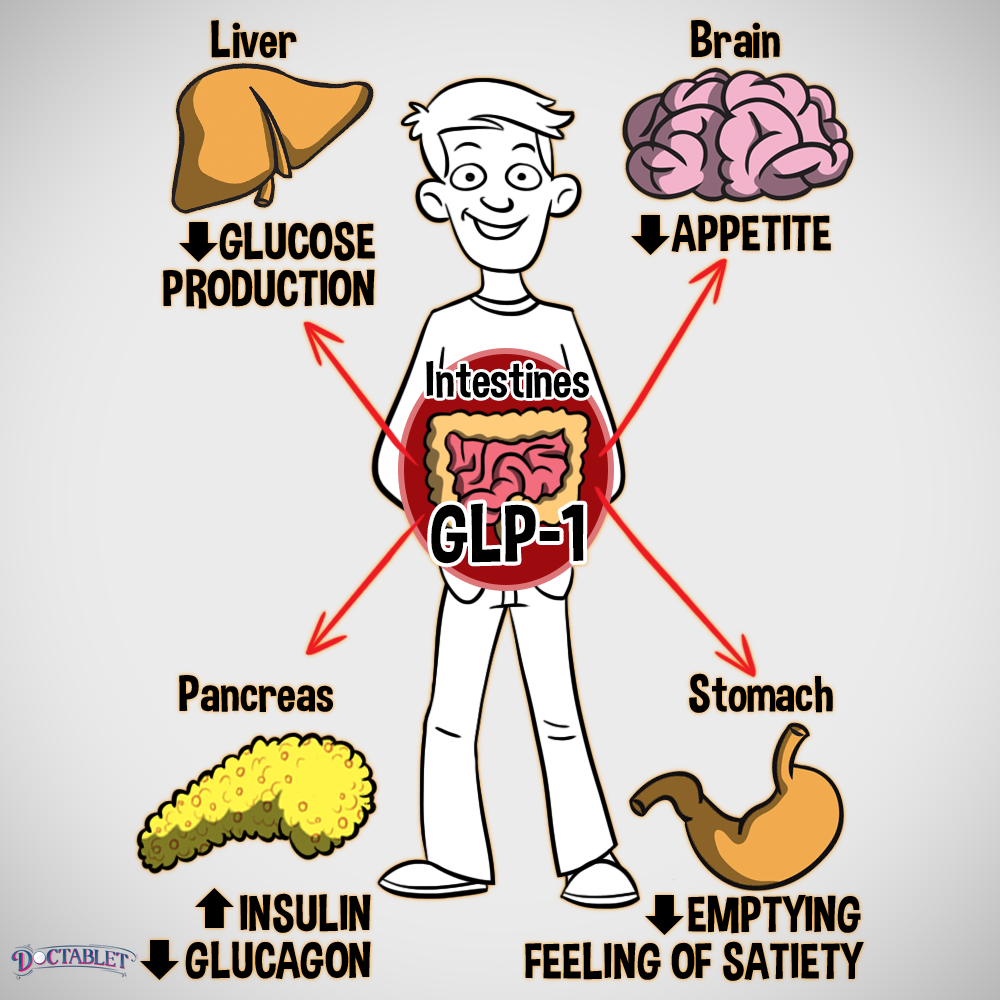

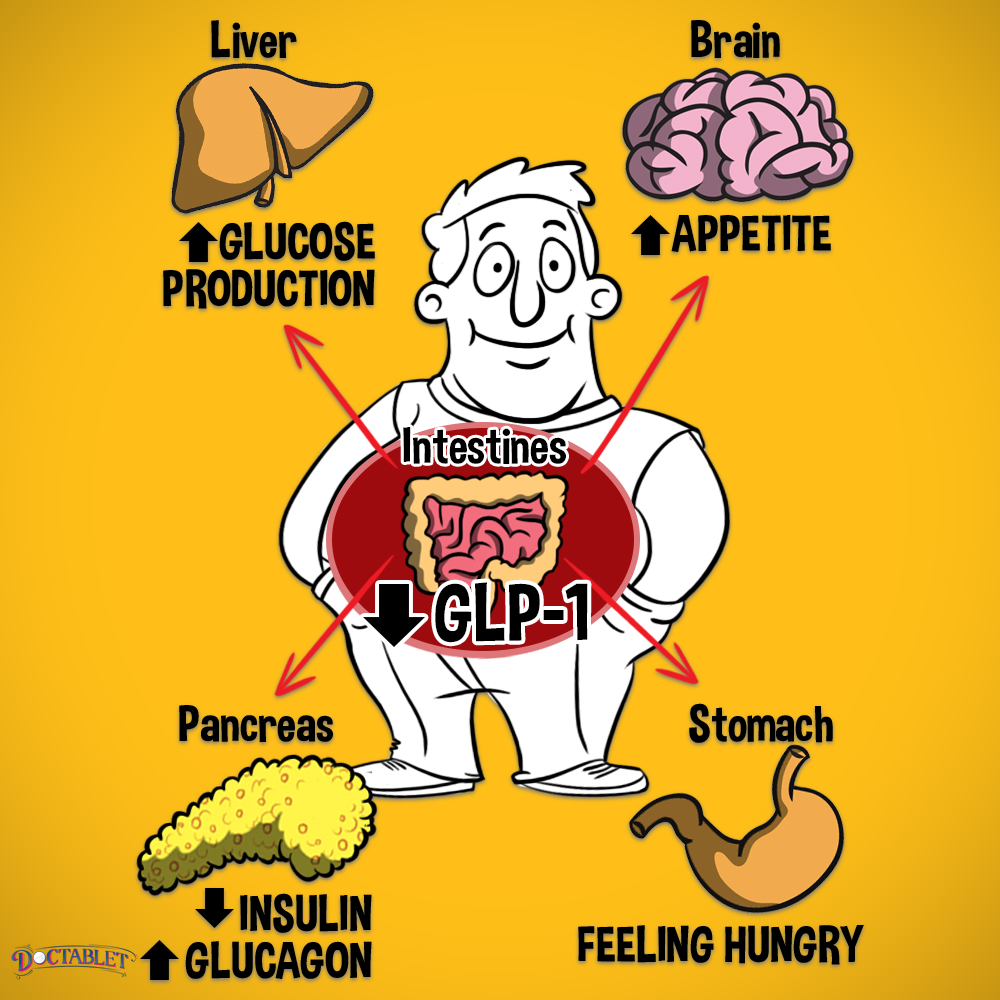

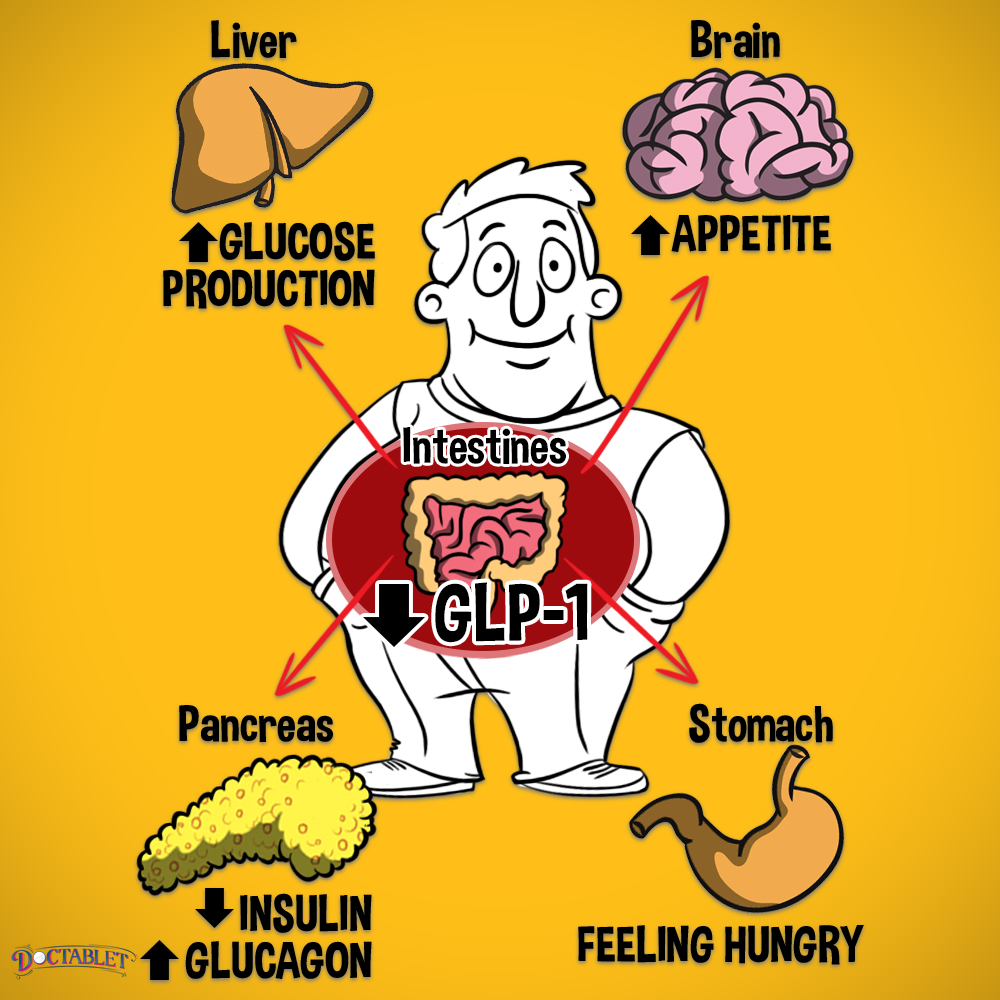

GLP-1 (Glucagon-like peptide-1) is a naturally occurring incretin hormone made in the intestine in response to food. GLP-1 is one of the two most important incretins—hormones that stimulate insulin secretion in response to a meal. But GLP-1 does more than simply increase insulin secretion. In fact, it has several important roles in the body. They can be summarized into two main functions.

GLP-1 affects levels of insulin and glucagon to decrease elevated blood sugar levels in two ways:

GLP-1 increases the body’s own natural insulin secretion in response to a meal.

GLP-1 lowers levels of the hormone glucagon after eating. Glucagon works opposite insulin and raises blood sugar levels, so deceasing glucagon levels helps to lower blood sugar.

GLP-1 increases satiety or makes an individual feel full

GLP-1 slows stomach emptying, so food is delivered more slowly to the intestines to continue digestion. If the food is digested more slowly, carbohydrate absorption is prolonged.

GLP-1 suppresses appetite in the brain’s hunger center (hypothalamus).

What is a GLP-1 analog/agonist?

GLP-1 analogs or agonists act like naturally occurring GLP-1 by stimulating the same receptor as a person’s own GLP-1 hormone. Rewind the clocks back to the early 1990s, when an endocrinologist discovered a special molecule similar to human GLP-1, which was being studied around the same time. Dr. John Eng found this special protein in the last place you could imagine—the saliva of the Gila monster, a poisonous lizard. This substance, called exendin-4, is 53% similar to human GLP-1 hormone, but is more resistant to being broken down. This makes it more useful as a treatment option. Scientists reproduced exendin-4 in the lab, calling it exenatide. Exenatide was first made available for type 2 diabetes management in 2005 as Byetta®, a twice-daily injection.

GLP-1 levels and type 2 diabetes

Turns out that patients with diabetes are not only likely deficient in their own GLP-1 hormone but, more importantly, the cells that make insulin are resistant to stimulation by GLP-1. This means patients might have less of this important hormone, and what they have left clearly does not stimulate insulin as well.

Why not just treat patients with the GLP-1 hormone?

The body’s own naturally occurring GLP-1 has a very short half-life in the bloodstream. Within minutes, hormones like DPPIV break down GLP-1. Due to this rapid degradation, treating patients with GLP-1 hormone directly has never been shown to be a useful option.

Share this with a patient or friend

Advertisement